Virgal Woolfolk of Innsbrook, tours the Lorraine Hotel in Memphis, Tennessee

By Sally Tippett Rains

As the Cardinals head to Jupiter, Fla., for spring training there are a lot of preparations being made. Whether rookies or seasoned professionals, the players will be spending about six weeks in Florida and most likely will be staying at a luxury hotel, condo or a leased home—wherever they decide they want to stay.

As we observe Black History Month, it’s worth noting that in the 1950’s and early 1960’s the black players would not be as free to make that choice. Many of the current players’ grandparents sadly would not have been welcome at most of the hotels where the white players stayed back then.

Jackie Robinson broke the major-league color barrier on April 15, 1947 as he took the field for the Brooklyn Dodgers on Opening Day. Robinson made his first appearance in St. Louis about a week later, on April 22. It would be nearly seven years later before Tom Alston became the first African American to play for the Cardinals, debuting on April 13, 1954.

Though they were playing on the teams, the black players still were not welcome to stay at the same hotels as their white teammates in spring training in St. Petersburg, Fla. during that time and into the 1960’s.

Bill White, the Cardinals’ first baseman at the time who later went on to become the president of the National League after a stellar broadcasting career, described what those years were like in his autobiography, “Uppity.”

White also was quoted in the “Cardinals 100th Anniversary” book by Rob Rains about the situation, noting that “We were the first team to integrate spring training.”

White also was quoted in the “Cardinals 100th Anniversary” book by Rob Rains about the situation, noting that “We were the first team to integrate spring training.”

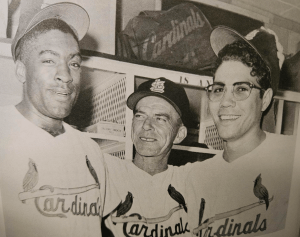

White is shown in a photo from the book. He is on the left, next to manager Johnny Keane and Julian Javier.

Though it is hard to take, this was a part of history and should be remembered by the younger generations. There was a fancy hotel called the Vinoy in St. Petersburg where the Cardinals trained. They, like many hotels of the time would not let black players stay there.

As White remembered it in his book, “The Cardinals finally demanded that the Vinoy Hotel would open itself to black players.”

“The hotel refused, so in order to help keep spring training in St. Petersburg, a local businessman bought a beachfront hotel called the Outrigger and made it available to all Cardinals players and their families, black and white,” White wrote about the 1961 event. “As a show of solidarity, players who usually stayed in private beachfront homes like Stan Musial and Ken Boyer also moved into the Outrigger.”

In the 100th Anniversary book, White also talked about that spring.

“Some of the guys like Boyer and Musial had been staying someplace else but they decided to come in and stay with everybody else,” White said. “The Cardinals were determined not to let their black players be treated like second-class citizens so they basically took over a hotel and everybody stayed there. We had cookouts every night and the players got to know each other, the wives were together and the kids all played together.”

This same kind of prejudice with the hotels was happening all over the United States and the players who came to St. Louis to play the Cardinals during the regular season had the same experiences: they were shut out of many of the hotels.

The Chase was an exclusive hotel that until the 1950’s only whites were allowed to stay there. While blacks were not allowed, the hotel owners did hire entertainers like Count Basie, Nat King Cole, Dorothy Dandridge, Ella Fitzgerald, Lena Horne and Eartha Kitt to perform there.

Even after blacks were allowed to stay in the hotel, historians have noted they were prohibited from using public areas such as the restaurants, bars and swimming pool.

So even when they were “allowed” at a fancy hotel they were still made to feel out of place there. For that reason many still chose to stay with black families who opened up their homes and provided them with food and a social atmosphere, like the Holly family.

“My Aunt Roberta and Uncle Lonnie Holly had a home on Page,” said Virgal Woolfolk, who grew up in Wright City. “When black ballplayers came to St Louis and were not allow to stay at the Chase with their white teammates, they would stay at Aunt Roberta and Uncle Lonnie’s home.”

We told the story last year of how Woolfolk’s relatives housed black players that came to town to play the Cardinals. In case you missed it, CLICK HERE.

“One of my favorite players who came out to my aunt’s house was Lou Brock,” said Woolfolk. “He was nice to us kids.

“The person who stayed at my aunt and uncle’s house but wasn’t very nice to us was Curt Flood, but it could have been due to the stress he was under. But Curt Flood is the reason the players have free agency.”

Woolfolk said that during Black History Month Flood should be remembered and honored for all he accomplished in his life.

“The other person we should not forget was Cool Papa Bell, who was friends with my dad and uncle,” he said.

Woolfolk said that by the the time he knew Bell, a Hall of Famer who played in the Negro Leagues, he was older and was working for the city of St Louis as a custodian.

“Mr. Bell was funny and would challenge us to races,” he said. “Of course he would let a little guy like me that wore a size ‘husky’– a large size for children my age– occasionally win.”

Players such as Willie Mays, Hank Aaron and Ernie Banks would come to town and stay on the second floor of the Holly’s home. Woolfolk was a child and he got to meet the players; and some of the white players like Musial would also come around. (To read more about this: CLICK HERE)

Black History Month follows the celebration of Martin Luther King Day and there were several notable things the civil rights leader did which happened in the month of February.

On February 1, 1965, the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. led more than 250 activists to the Dallas County Courthouse to register to vote. There was no violence and they had a peaceful demonstration but were arrested and charged for parading without a permit.

King had another meaningful thing occur in February when, according to a research paper from Stanford, “On 4 February 1968, Martin Luther King, Jr., preached ‘The Drum Major Instinct.’”

He was preaching at the famous Ebenezer Baptist Church, and in the sermon he said “I’d like for somebody to say (at my funeral) that day that Martin Luther King Jr. tried to love somebody.”

Ironically two months later (April 4, 1968) he was assassinated, and parts of that sermon was played at his funeral service which took place at the same church on April 9, 1968.

Ironically two months later (April 4, 1968) he was assassinated, and parts of that sermon was played at his funeral service which took place at the same church on April 9, 1968.

Woolfolk remembers when he was 10 years old and King was to come to St. Louis to speak as part of a Saint Louis University speaker series.

“When I was growing up, my aunt and uncle and folks of their generation were not so keen on Dr. King coming to St Louis,” he told STL Sports Page. “Remember there were riots and retaliatory attacks by white folks not just with physical violence, but economic sanctions against black businesses and with employment.”

Nevertheless King did come to St. Louis and there are still who remember being in the 3,000-plus crowd. According to an article in SLU’s alumni newsletter, “During visits to St. Louis, he spoke at Washington Tabernacle Missionary Baptist Church, United Hebrew Congregation, Temple Israel and Christ Church Cathedral, calling on these institutions to challenge their own prejudices.”

Two days after he was in St. Louis he won the Nobel Peace Prize, so many St. Louisans felt a special closeness to him after that and also felt a personal loss when he was shot and killed at the Lorraine Hotel in Memphis in 1968.

For Woolfolk, who now lives in Innsbrook, Mo., Dr. King’s death was the realization of more than just losing a national icon upon whom his family and friends had faith in. Woolfolk is shown in the photo at the top of this article years later touring the Lorraine Hotel which stands today just as it did that fateful day that was photographed so many times.

The assassination involved a myriad of complicated feelings for Woolfolk iliving n his childhood home of Wright City.

“Growing up in Wright City, one of my dearest friends was a kid by the name of Jeff Ray,” Woolfolk said. “He lived with his brother and mother and Hispanic step-father just west of our school in an area that today is the intersection of Bell Rd. and Westwood Rd.

“There is one day in 1968 that will be etched in my mind forever. Like any other day– but this was one specific day I remember–a group of us were playing in the Ray’s barn across the street from his house. There was Sam Park, Gary Perkins, Michael McLaughlin and Dennis Meyer, my group of pals at this time.”

Wookfolk said that all of these kids would grow up to have remarkable lives. Park graduated from the Naval Academy and worked on facial recognition; Perkins was E-8 in the Air Force who became an electrician with incredible accomplishments and recently celebrated 50 years of marriage to his childhood sweetheart. McLaughlin was a handsome, talented baseball player whose life was cut short due to cancer and Dennis Meyer a successful farmer and community leader in Wright City.

“That one day I was out playing with my friends and having a regular carefree, youthful day, but the next day, the world changed forever.”

The next day was April 4: the day the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King was assassinated. It was completely devastating to all Americans especially any black family.

“Dr King had been murdered in Memphis for helping black Americans receive equal rights and equal pay,” said Woolfolk.

While the grownups were devastated, they wanted life to go on as normal for the children. After school let out, Woolfolk and his buddies rode their bikes out to Jeff’s house to work on their FFA animal projects. As they parked their bikes they saw an odd sight.

“Coming down the hill we saw all these news trucks and reporters from KMOX Channel 2, and KSD Channel 5,” said Woolfolk.

It had been a shocking day with King’s death and now all these television vehicles. There was even more devastating news to come for him.

“Come to find out, Jeff Ray was the nephew of James Earl Ray—the man who murdered Dr. King. Jeff Ray and his family’s life changed forever in Wright City, that day” said Woolfolk.

His young mind could not fully comprehend it all. The trucks and the reporters, and then national and international media outlets were in front of their house for days.

“Eventually, Jeff told us that his own dad and his uncle (James Earl Ray) had been in and out of jail and that was why his mother divorced his father. School ended about a month later, and we never saw or heard from Jeff Ray or his family ever again.”

Years later, Woolfolk was in the Navy traveling from San Francisco to San Diego when he had quite an encounter.

“Sitting next to me was this older well-dressed black man who was on his way to San Diego to campaign for a peanut farmer and former Navy lieutenant by the name of Jimmy Carter,” he said. “Through our conversation I found out that man was Dr King’s father.

“We had a great conversation and he told me not only was his son murdered, but six years later his wife was murdered in their church.”

They had a long conversation and the elder King gave a young Petty Officer in the Navy some advice.

“He made me promise to ‘rise and do great things,’” he said. “I have done my best.”

“So while I know everyone has their memory of where they were that day or how they felt when they got the news that Dr. King was killed, this is my recollection of what I experienced the day Dr King was killed.”